This fuller immersion is part of what marks the ancient experience of Holy Week as a sort of pilgrimage. This change from the usual patterns of Mass and prayer to something more solemn is intended to catch the attention of the Christian and to draw them into a much deeper experience of the mysteries of our salvation. Standing in the places where these things actually happened in history, walking where Our Lord Himself walked… and died… it starts to be a little less strange that people might be moved to tears at the Gospel of the betrayal of the One who freely gave His life for each one of us.

Returning to the events of Thursday – after the Mass behind the Cross, Egeria describes people rushing home to eat, before hurriedly assembling at the Eleona, where they sing hymns and antiphons as well as reading scripture passages and offering various prayers well into “the fifth hour of the night”, recalling the discourses recorded in Matt 26 and Mk 14. An additional source, the Armenian Lectionary, indicates Psalm 118 and Luke 22:39-46 as readings for this celebration.

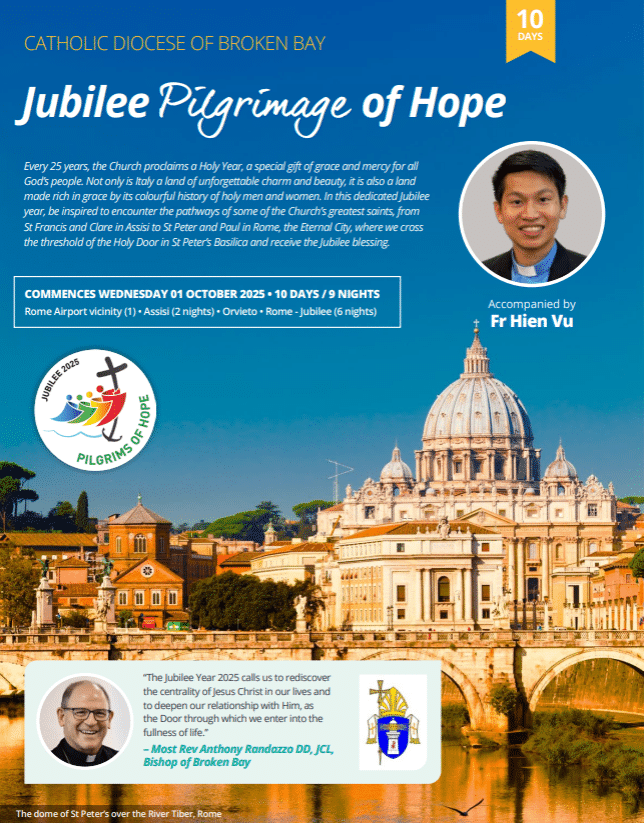

In the sixth hour of the night, they all process from the Eleona to the Imbomon (you can see in the image above how close these two churches are – only about 60-70 metres apart… in today’s local terms it might be a little like walking from a parish church across the carpark to a parish hall on the other side of the same property!) The Imbomon would have been a brand new church at the time that Egeria visited, having been completed sometime within 10 years prior to her visit, funded by a wealthy Roman woman named Peomenia, who had ties to the Imperial Family. More hymns, prayers, and readings occur here.

At the hour of the cockcrow, everyone processes down from the Imbomon – still singing hymns – towards the place in Gethsemane where Jesus prayed. Egeria describes this portion of the procession as very slow, indicating that the people are fatigued from their vigil at this stage, and because it is a bit of a precarious descent down from the mountain. She reports that “over two hundred church candles are ready to provide light for all the people.” Upon reaching Gethsemane, the Gospel account of the arrest of the Lord is read… accompanied by such moans and weeping from the crowd that it “can be heard practically as far as the city.” Again singing hymns, everyone processes back tot he city gates on foot – “the old and the young, the rich and the poor, everyone; and on this day especially no one with draws from the vigil before early morning.” Their arrival in the city coincides with first light, and they process behind the bishop to the Cross.

Good Friday in the Early Church

It is now Good Friday and the people have kept vigil all through the night. Before the Cross, the Gospel account of the Lord being brought before Pilate is read. Egeria tells us:

Afterwards, the bishop addresses the people, comforting them, since they have labored the whole night and since they are to labor again on this day, admonishing them not to grow weary, but to have hope in God who will bestow great graces on them for the efforts.”

The people go from the Cross to pray at the pillar where the Lord was scourged, after which they return to their homes for a very brief period of rest.

At the “second hour” (it seems as though the hours are counted from sunrise) the people assemble at Golgotha. Egeria describes a large chair/throne set up for the Bishop behind the Cross, with a table covered in linen cloth set before him, with deacons in attendance. What happens next will be familiar to anyone who has attended a 3pm service on Good Friday in past years:

A gilded silver casket containing the sacred wood of the [true] Cross is brought in and opened. Both the wood of the cross and the inscription are taken out and placed on the table. As soon as they have been placed on the table , the bishop, remaining seated, grips the ends of the sacred wood with his hands while the deacons, who are standing about, keep watch over it… It is the practice here for all the people to come forth one by one, the faithful as well as the catechumens, to bow down before the table, kiss the holy wood, and then move on.”

Egeria indicates that the reason for the deacons in attendance is that someone once took a bit and stole a piece of the holy cross – the deacons stand guard in case anyone dares to try that again. She also explains that, whilst people kiss the cross, or rest their foreheads against it, nobody dares to touch the cross with his or her hands, such is their reverence. After venerating the Cross, the phial of oil with which the ancient kings were anointed, and the ring of Solomon, are both extended by a deacon to be kissed by members of the faithful.

The process of this veneration takes several hours; at the sixth hour, this concludes and the faithful go before the Cross, regardless of the weather conditions despite being an uncovered courtyard extending between the Cross and the Anastasis. Egeria describes very tightly packed crowds. For the three hours that follow, nothing else is done but the reading of passages from Scripture, taken from the Psalms, Epistles and Acts, wherever they mention the Passion. Then the Gospel of the Passion is read.

After this, when the ninth hour is at hand, the passage is read from the Gospel according to Saint John where Christ gave up His spirit. After this reading, a prayer is said and the dismissal is given.

The people then gather in the Martyrium, where the various daytime prayers and exercises that occurred on earlier days in the week are carried out. The people then process to the Anastasis, where the reading of the Gospel where Joseph of Arimathea petitions Pilate for the body of Our Lord so that He can be placed in the tomb. After prayers, the catechumens are blessed and all are dismissed.

“Those who are able” and “the clergy who are either strong enough or young enough” (recognising the fatigue of many of the people) then go to the Anastasis to keep vigil.

Holy Saturday in the Early Church

The customary prayer services of the third and sixth hours that are described on other days both occur on Holy Saturday, but there is no service at the ninth hour, since preparations are being made for the Easter Vigil that will take place in the Martyrium. Egeria notes that the vigil is celebrated in Jerusalem exactly as it was celebrated in her homeland, except that the baptism of the catechumens is more elaborate here in the Holy Land. The neophytes are then led first to the Anastasis with the bishop, who goes within the railings of the Anastasis to pray for the neophytes, after which he returns with them to the Martyrium for the Vigil Mass to be completed.

Easter Octave

Egeria reports that the Easter Octave was observed in similar fashion to the way it was done in her homeland, noting also that the decorations in the Churches were the same as the decorations used during Epiphany. On the first Sunday, as well as Easter Monday and Easter Tuesday, the Mass is celebrated at the Martyrium, after which everyone processes to the Anastasis singing hymns. On Wednesday of Easter, Mass is celebrated in the Eleona; on Thursday, in the Anastasis; on Friday at the pillar where Jesus was Scourged and on Saturday, before the Cross. On Low Sunday, the final day of the Octave, Mass is again held in the Martyrium. The reading for Low Sunday is the Gospel relating the account of “doubting Thomas.”

After lunch on each day of the Octave, the bishop leads all the newly baptised up to the Eleona where hymns are sung both there and in the Imbomon, after which they gather at the Anastasis for Vespers.

What can we take away from Egeria’s experience?

The Early Christians attached significance to different places, and frequent processions between those places were a feature of their liturgical life. There was nothing lazy or convenient about their worship – when Egeria records that outdoor ceremonies occurred regardless of the weather, it suggests that perhaps at some point during the Holy Week she spent in Jerusalem, they experienced rain and remained steady in their worship despite the rain beating down upon them! The immersive nature of their celebration of the mysteries enabled the faithful of that time to experience genuine sorrow at the injustices hurled at the Lord they loved, manifested outwardly in their open weeping at the betrayal, the arrest, and the cruelty of his torment and execution.

In some ways this is a little bit of a challenge to each one of us – do WE feel as keenly the horror at what was done to Our Lord? Do live our Easter Weekend with generosity, immersing ourselves as fully in our local celebrations as we possibly can?

We are all invited to consider approaching the Holy Week liturgies as a sort of Pilgrimage during the Holy Year of Jubilee!